Revolution: a drastic shift in who or what elements control the narrative of human history.

My definition of revolution is closely related to how we record and interpret human experience and knowledge over time. An event that occurs now might not be considered a revolution until a thousand years later when that event is considered to be a significant, notable change in how we understand human experience. Revolution is a finely weaved synthesis of current understanding of our past and an unknown knowledge of our future perceptions. This definition is descriptive, not prescriptive, because it only attempts to identify how the term is used, not how it should be used. My definition intentionally leaves room for differing classifications of revolution as our understanding of our past changes with time.

Consider how we identify revolutions similar to how we identify the finest of fine wines; each bottle is filled with different grapes and aged in varying climates and conditions. After one year, each bottle is tasted. Some of the bottles taste amazing and are labeled as ‘revolutions’ because they best match the contemporary tastes and preferences. The other bottles are left to age and after another year, new bottles are added to the collection of fine wines labeled as ‘revolutions’ because they now match the tastes and preferences. Different bottles are added periodically as their flavors age and our tastes adapt. Bottles that were once discarded because they hadn’t matured may have developed to match contemporary tastes at a much later date than other bottles. Bottles that once were embraced may spoil over too long of a period of time and be thrown away in disgust.

Similarly, the concept of revolution is dynamic and perpetually changing. An event that occurred 200 years ago that is peripheral in our understanding of the human experience and human history may come to the forefront of our concept of revolution in 50 years pending changes in our tastes and ideas of what makes us human. That being said, ideas or events considered revolutionary now may spoil with age and be discarded from our understanding of the human experience.

Lapham addresses this idea in his book, Lapham’s Quarterly. He points out that our definition of what a revolution is has lost meaning because everything has been labeled and marketed as revolutionary. For example, Tesla is considered revolutionary now because the company is creating a new idea of what the electric car is. But if in 50 years, the movement started by Tesla hasn’t made any significant progress in the fight against climate change, then it will no longer be considered revolutionary. Lapham uses similar examples in his book such as the guillotine. At the time of its conception, it was a tool. Now, it’s considered a symbol of revolution, control, and punishment. It has aged into a representation of a time period in history.

Revolutions send ripples throughout society, altering activities, ideas, and things that seem distant and detached from the original revolutionary event. My final research essay delves into the broad sweeping revolutionary impact of social media. Social media platforms have fundamentally changed how humans interact with each other, accelerating the exchange of information and establishing connections between billions of individuals. A quintessential example of the revolutionary capabilities of social media is the Arab Uprisings in 2010-11 which were facilitated by the rapid spread of information and dissent on social media. These uprisings deposed authoritarian regimes in Tunisia and Egypt and sparked civil wars in several other countries, permanently altering the power relations of the entire region. This all seems overwhelmingly positive, but social media has also enabled the dissemination of evil and extremist ideologies. My paper examines the Christchurch mosque shootings and the role of social media in promoting violence and promulgating extremism. All of this is to say that the impact of revolutions encompass every aspect of life and while they can advance good causes, they can inadvertently advance causes diametrically opposed to progress.

In Unit 1, Professor Quillen discussed how our definition of what being human means has changed over time. Specifically, we discussed how the enslavement of Africans was considered revolutionary at its time because it developed a system of labor in the Americas that allowed the colonies to prosper. In retrospect, this so-called ‘revolution’ is considered an atrocity of the highest degree. Instead, emancipation and the instillment of rights for former slaves is what’s considered revolutionary today. This is just one example of the dynamic nature of identifying revolutions. Unit 2 offered more great insight into how we define revolutions. The Scientific Revolution, at its time, was a small group of astronomers, chemists, and other scientists who negated the power and ideas of the church. We only consider it revolutionary now because we have incorporated these sciences into the fabric of society. Unit 3 presented an example of revolution that was much more rapidly recognized than other examples of revolution. The Rwandan Genocide was ignored by the international community in its early phases, but once months and years passed and the stories had been disperesed, it was and is considered a defining piece in understanding the human experience and history. Finally, in Unit 4, we can use the Freedom Riders as an example of the dynamic nature of revolution. The Freedom Riders might not have thought they were participating in a revolutionary movement when they sat in at restaurants. To them, they were simply trying to ascertain their rights. However, we now recognize the movement as revolutionary because it significantly shifted the narrative of human experience and history.

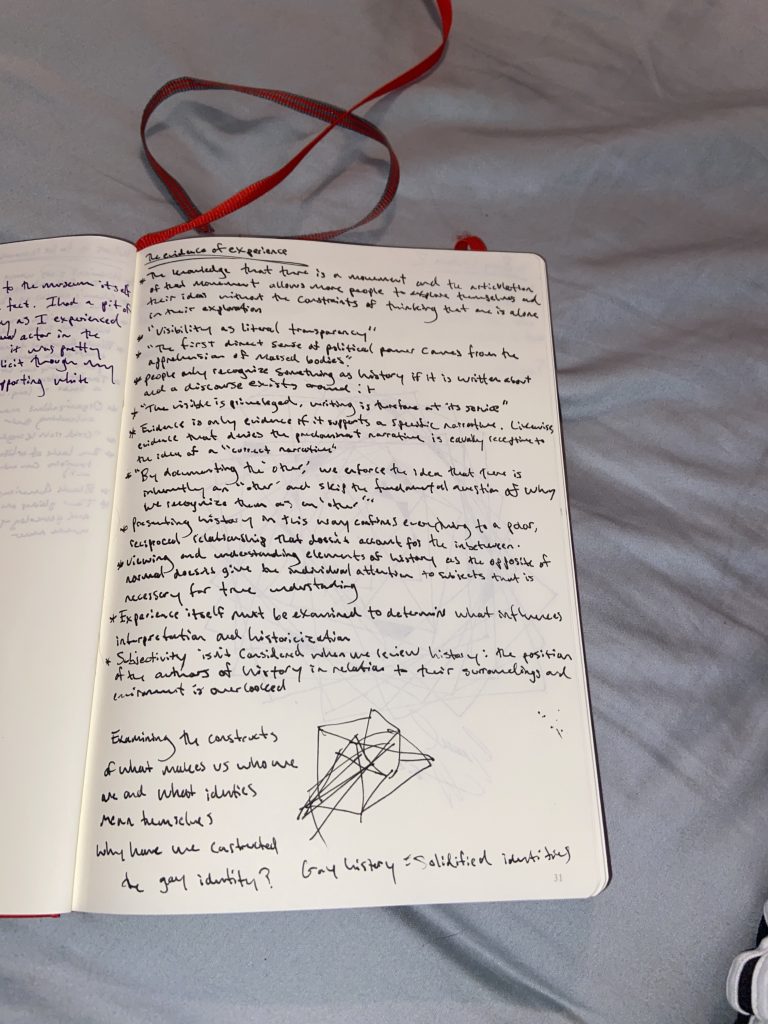

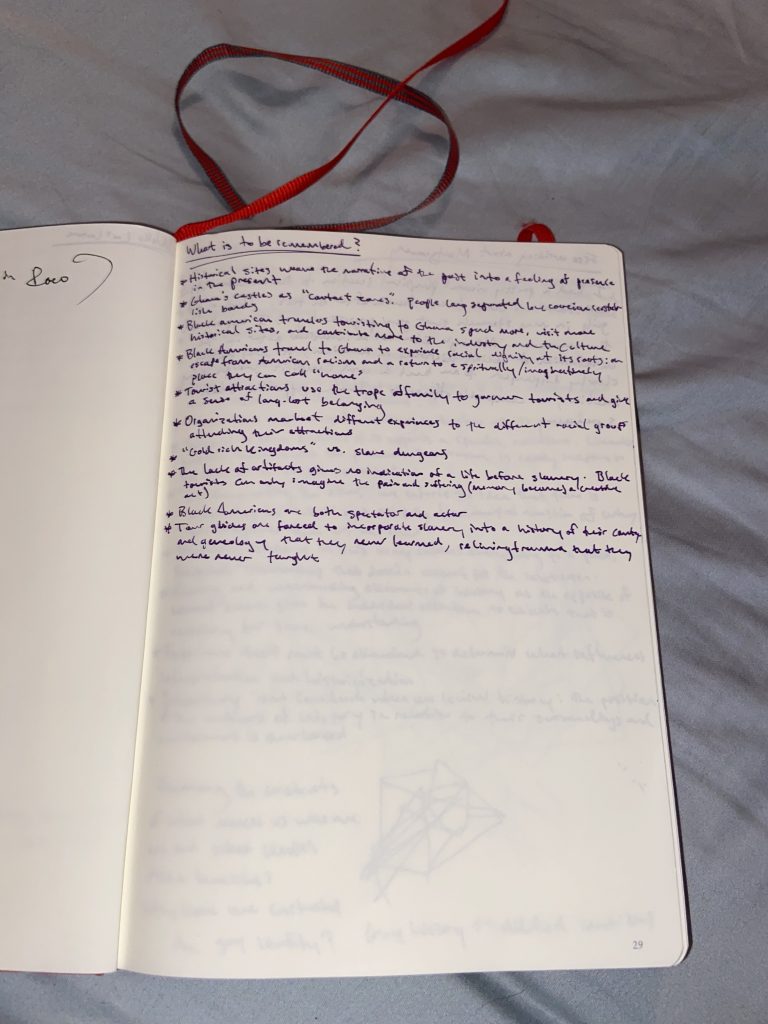

Unit 5 with Professor Bory concerned the documentation of history. In “The Evidence of Experience,” we read about what constitutes a dominant historical narrative and how that narrative constrains other parts of history into the category of an ‘other.’ This construct of mainstream history versus everything else gives history a particularly polar nature and when the poles flip and the ‘other’ is noticed and documented, it could be classified as a revolution. I identified some connections between unit 5 and unit 6 with Professor Munger, namely that the sciences and the humanities are often seen as opposites when in reality, there are numerous intersections between the two. CP Snow’s “Two Cultures” exemplifies this by detailing the two subjects’ opposition and then analyzing their similarities. Unit 7 with Professor Ewington focused on the repercussions of the Bolshevik Revolution. The power shift led to the Terror of the 1930’s in which repression, extrajudicial state sponsored violence, and arbitrary imprisonment were rampant. I thought that this exhibited the rippling effects of revolutions and how they can inadvertently regress parts of society. Finally, unit 8 with Professor Denham covered the RAF and their ‘revolutionary violence.’ I thought that it was interesting that the violence was considered revolutionary despite its failure to generate real change. This realization helped me identify a key component in successful revolution: mass mobilization. Without popular support, revolutionary attempts are considered radical extremism.

Lapham, Lewis. Lapham’s Quarterly, Volume VIII, Number 2 (Spring 2014). Revolutions. New York: America Agora Foundation, 2014.